PHM Intern’s History Blog

Touring the Hudson: The Charm of the River Itself

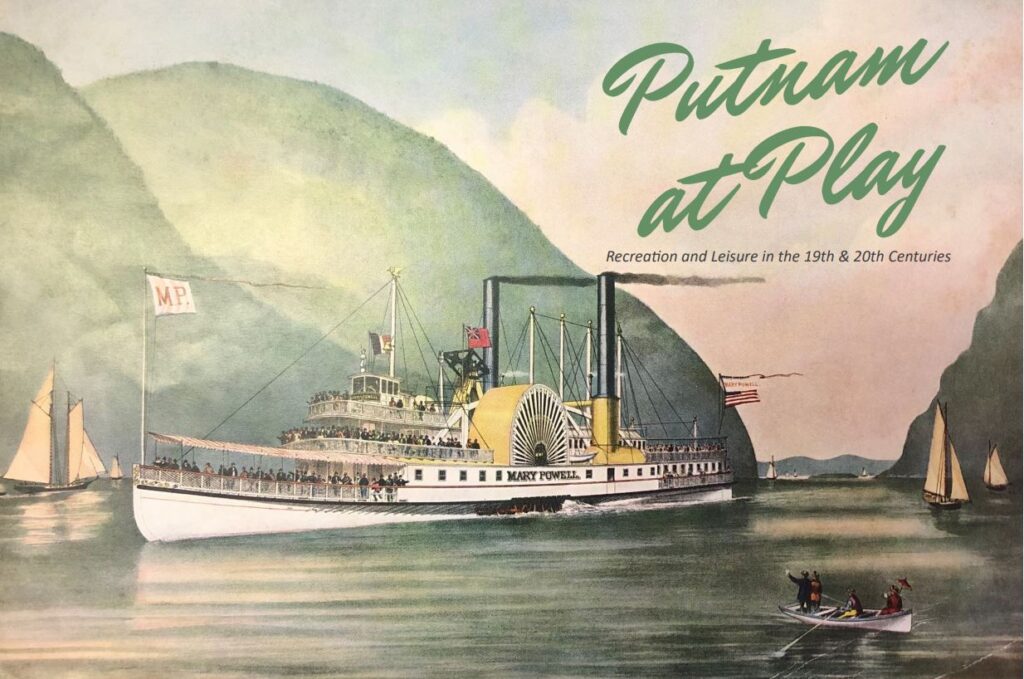

As the summer heat begins to bear down on us, it’s interesting to recall that people in the 19th and 20th century traveled north of New York City to visit all along the Hudson River for some respite – including Cold Spring and the Hudson Highlands. Not only did they recognize that the Hudson Highlands were beautiful, but the journey itself could be refreshing. While trains were fast and convenient, steamboats offered comfort and entertainment in order to appeal to expanding middle-class tourism. Travel to resorts (as seen in the museum’s current Putnam at Play exhibition) could be part of these excursions, but day-trips to take in the views were popular as well.

A sail on the river gives renewed vigor to the children and enables them to withstand the trying heat of the season.

— The New York World.1

Romantic Views

View of Philipstown from West Point, Robert Walter Weir, oil on canvas, c. 1850-1870 (PHM)

Hudson River School Painters, such as Robert W. Weir, arguably made this region famous. The oil paintings, which were displayed in NYC gallery windows, did as much advertising as engraved illustrations found in guide-books and periodicals.

Painters were eager to capture the idyllic landscape before it vanished through industrialization. This popularized many Hudson River towns. Rather than merely observing, however, tourists knew they could comfortably immerse themselves in picturesque views.

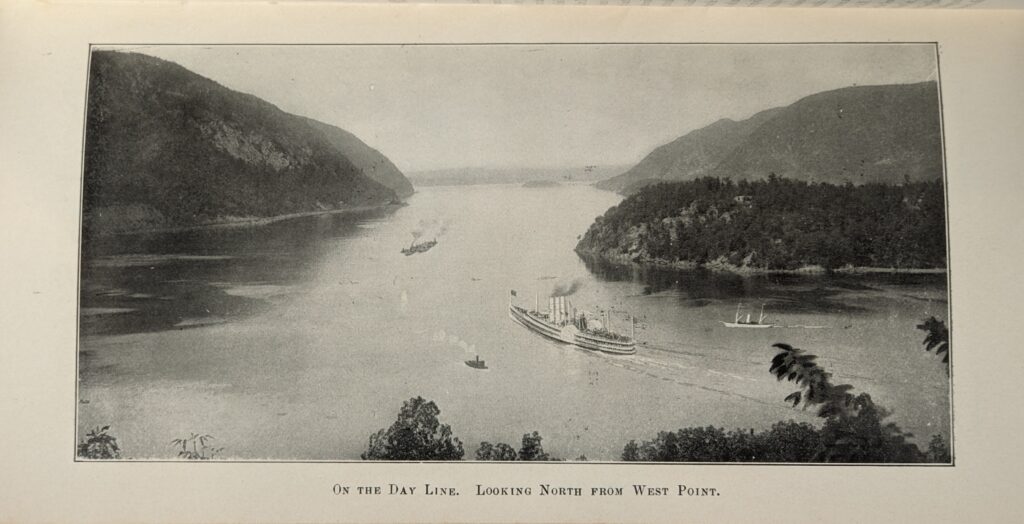

Views from West Point were a popular scene for painters, and their work influenced artists for decades to come.

Booklets, Brochures, and Guides

Hudson River Day Light Booklet, Summer 1905 (PHM)

In addition to paintings, pamphlets captured the attention of tourists by advertising the steamboats. Photos and illustrations within helped capture the atmosphere of the journey, not only reproducing the beautiful views to be taken in but the opulent interiors as well. The view looking north from West Point is very similar to those painted by Hudson River School painters, better bridging the imagination and the reality which was promised.

The Hudson River Day Line was only one of the many steamboat lines which ran along the Hudson, and as the name suggests offered only day service, stating in an 1898 booklet that there was “no accommodation for passengers [who wished] to remain on board over night.”2 There was however a Hudson River Night Line which could still offer some of the same sights though in the dark or a merely peaceful means of travel.

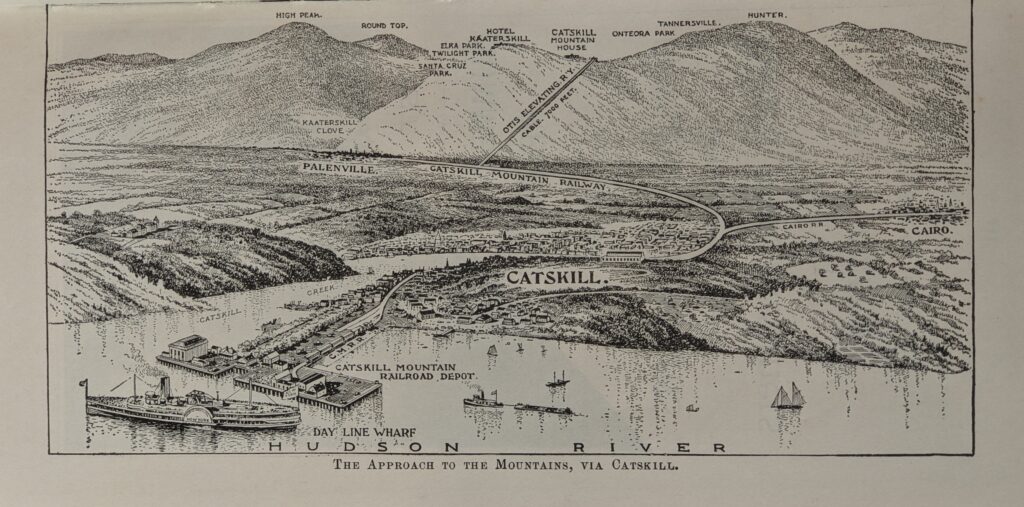

Descriptions of various destinations and experiences along the Hudson River were published in booklets accompanying a route (several of which are on display at the museum). Such publications could give the tourist another connection to the area before they ever set foot on the dock. They advertised destinations such as New York, Yonkers, West Point, Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, Kingston Pt, Catskill, Hudson, and Albany. Other lines were available, but almost always traveling one way from New York to Albany took about nine and a half hours. Trips could be expanded further using canals and railways (as depicted below in the elevation illustration from the Catskill dock to the resort) to take one further afield.

For New Yorkers traveling round trip to West Point, just across the river from Garrison, fare would have been $1 in 1898, just over $35 today. A round trip to Catskill, a popular setting in paintings from the Hudson River School, would have been $1.50 in 1898, over $50 today.3

Hudson River by Day Light Booklet, 1898 (PHM)

Embarking on the Journey

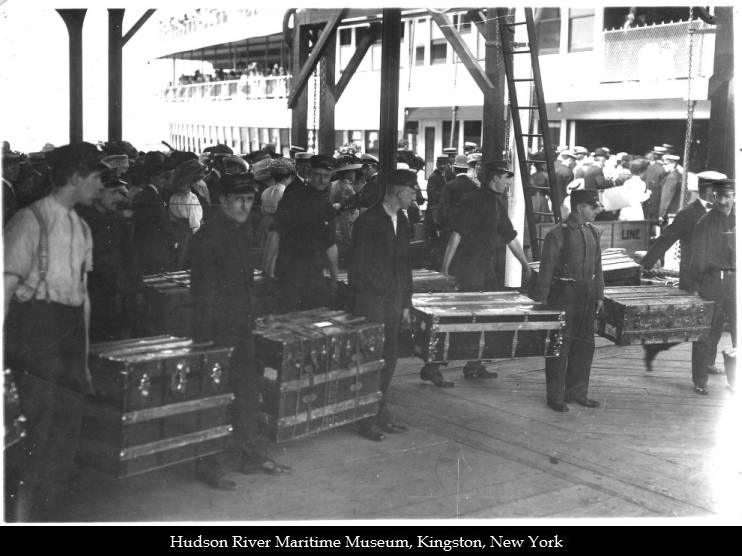

Passengers and luggage boarding the Hudson River Day Line steamer

on different gangplanks, photograph, early 20th century (HRMM)

While steamboats tried to appeal to travelers’ desire for peace and respite, the reality could be much more lively. There could be a spectacle on the docks as trunks were loaded using a ‘human-chain method,’ the decks crowded with fellow passengers and the crew working to keep the ship on time and the passengers comfortable.

One passenger wrote the following:

Leaving the Great Metropolis in our wake, we head due North, and viewing the beautiful panorama behind us, of wharves, shipping and great warehouses, extending for miles on either side towards New York Bay, our steamer rapidly approaches the finest scenery in the world… 4

The season could vary greatly in how many passengers were carried, but for peak travel years the Day Line carried 134,660 passengers in 1867, 173,000 in 1876 and 192,000 in 1892.5

An early 20th century photograph from the PHM collection shows people sitting on a deck of a steamer. A pilot house can be seen in the background. Along with the souvenir magazines and postcards, photos and sketches were mementos of the trip.

Aboard the Steamboat

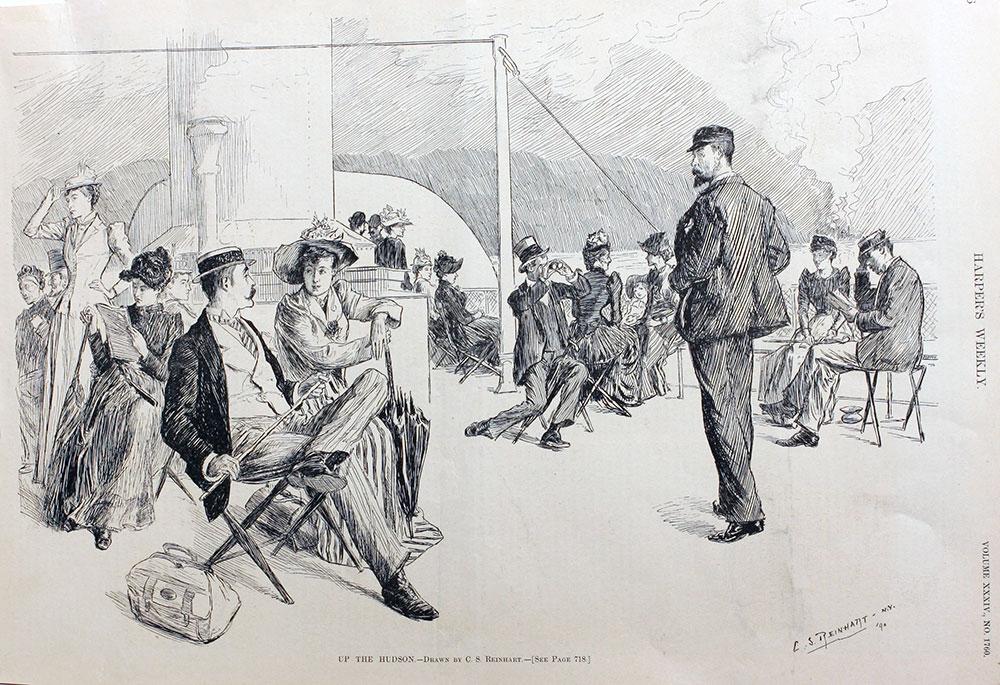

“Up the Hudson,” C. S. Reinhart, Harper’s Weekly, 13 September 1890 (Antipodean Books)

Aside from illustrations, newspaper articles indicated the type of people who were to be found on steamboats. A more refined type of person went on such journeys, was the implication, further elevating the status of steamboats:

The Albany day boats are doing an unusually large business. … The excursionists are of the better class — people who take more interest in the beauties of nature than they do in whisky.

— The Newburgh Daily Journal.3

The world of glamor and leisure was opening up to more people, however race and economic status were still limiting factors and steamboat tourism was no exception to this.

While it is clear that people of color also enjoyed traveling by steamboat, the experiences of Black passengers could vary greatly from prejudiced treatment, forcing them to travel in steerage below deck, to peaceful and amiable journeys traversing the entire ship, or ones that were not notable at all. Most of the documentation which exists alludes to Black workers on the docks or the steamboats themselves, but there are primary sources which indicate that steamboats were not segregated in the 19th century. An account given of a harrowing journey taken by the abolitionist and former enslaved man, Frederick Douglass, describes crew pulling him from his chair and forcing him to leave the dining room.6 Unequal treatment of Black tourists was often out of the travelers control and depended on several factors including the prejudices of the captain and conforming to such a self-restricted expression that appeased white passengers.

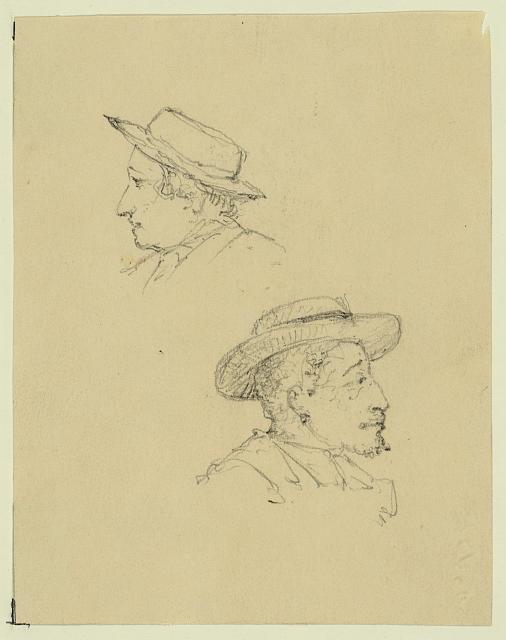

While photographs were becoming more popular, some travelers would capture the likenesses of their fellow passengers in sketches and illustrations as a means of entertainment. See below the drawing by George Wallis made in 1853 which depicts a “white seaman” and a person of color.7 Though made on the Potomac River, such a sketch may reflect the reality of traveling on the Hudson River as well, even if it is unclear if these men are workers or passengers.

White seaman and cold. [e.g. colored] man on board steamboat on Potomac, Washington to Aquia Creek Virginia, George Wallis, 26 June 1853 (Library of Congress)

Black tourists had as much of a desire for peaceful respite, if not more than other 19th century tourists. While public parks in New York City might turn away Black visitors or else assault them with open hostility, privately rented groves, such as Dudley’s Grove in Hastings-on-Hudson, were havens set up specifically for Black tourists and offered refuge not only from racism but crowded and unsanitary city life as well.

On chartered steamboats and in privately rented groves, Black New Yorkers could enjoy blooming landscapes together, away from the judgmental eyes and clenched white fists that greeted them whenever they went outdoors in the city. Excursions offered Black people the chance to breathe—and not just the fresh air that was scarce in Manhattan.

— Refuges from Racism Along the Hudson River by Marika Plater8

To learn more about Black tourism on steamboats, check out the Hudson River Maritime Museum’s blog post, detailing the ways in which this form of travel provided Black New Yorkers with refuge.

A Bustling River

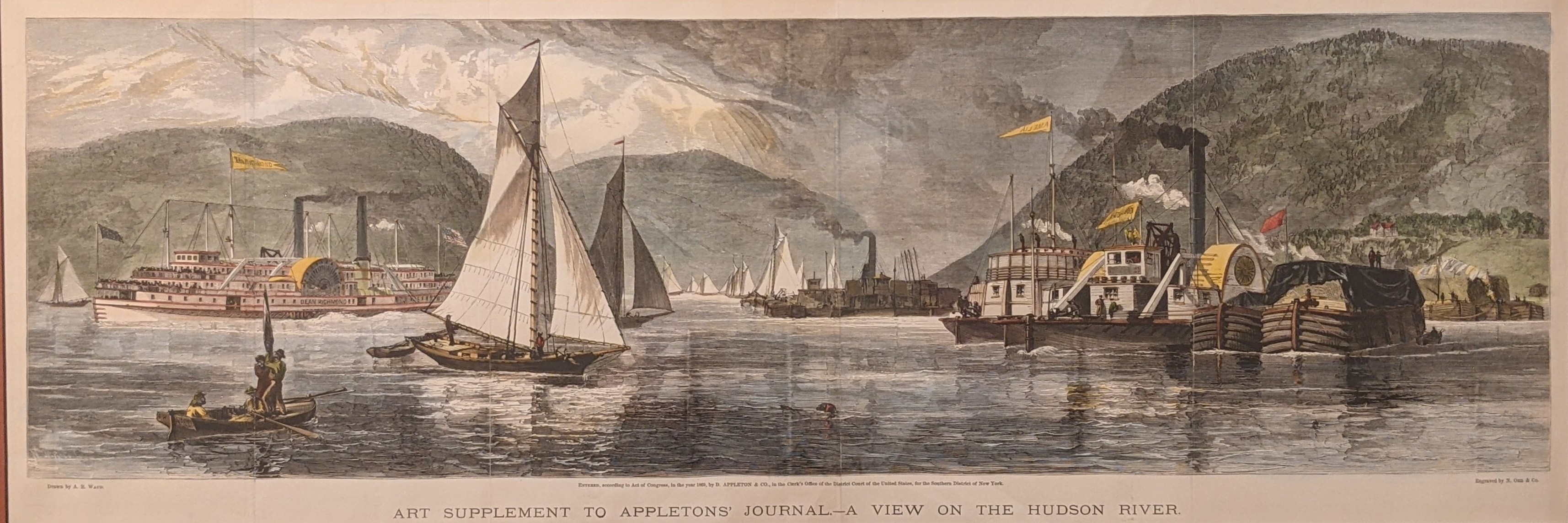

A View on the Hudson River (Appleton Journal View, Litho Print) 1869

As a major thoroughfare for trade and commerce, the Hudson River could at times be quite hectic. This busy scene provides a stark contrast to advertisements of tranquil travels. Tourists were trying to enjoy fresh air and distract oneself from urban life, but the picture suggests smoke from other boats or noisy commotion on the river may have been a reminder of industry and urban life. However, some probably enjoyed these displays of a thriving Hudson River Valley. In the same way a bustling dock showed off the efficiency of river travel, seeing the grandeur of vessels in action must have been thrilling.

In a quote from Walt Whitman regarding his 1878 sail on the Mary Powell, he remarks that:

On the Mary Powell, enjoy’d everything beyond precedent. The delicious tender summer day, just warm enough — the constantly changing but ever beautiful panorama on both sides of the river — (went up near a hundred miles) — the high straight walls of the stony Palisades — beautiful Yonkers, and beautiful Irvington — the never-ending hills, mostly in rounded lines, swathed with verdure, — the distant turns, like great shoulders in blue veils — the frequent gray and brown of the tall-rising rocks — the river itself, now narrowing, now expanding — the white sails of the many sloops, yachts, &c., some near, some in the distance — the rapid succession of handsome villages and cities, (our boat is a swift traveler, and makes few stops) — the Race — picturesque West Point, and indeed all along — the costly and often turreted mansions forever showing in some cheery light color, through the woods – make up the scene.9

Among the steamboats that sailed the Hudson River, the Mary Powell was one of the most influential ships and adored by many passengers apart from Whitman.

The Queen of the Hudson

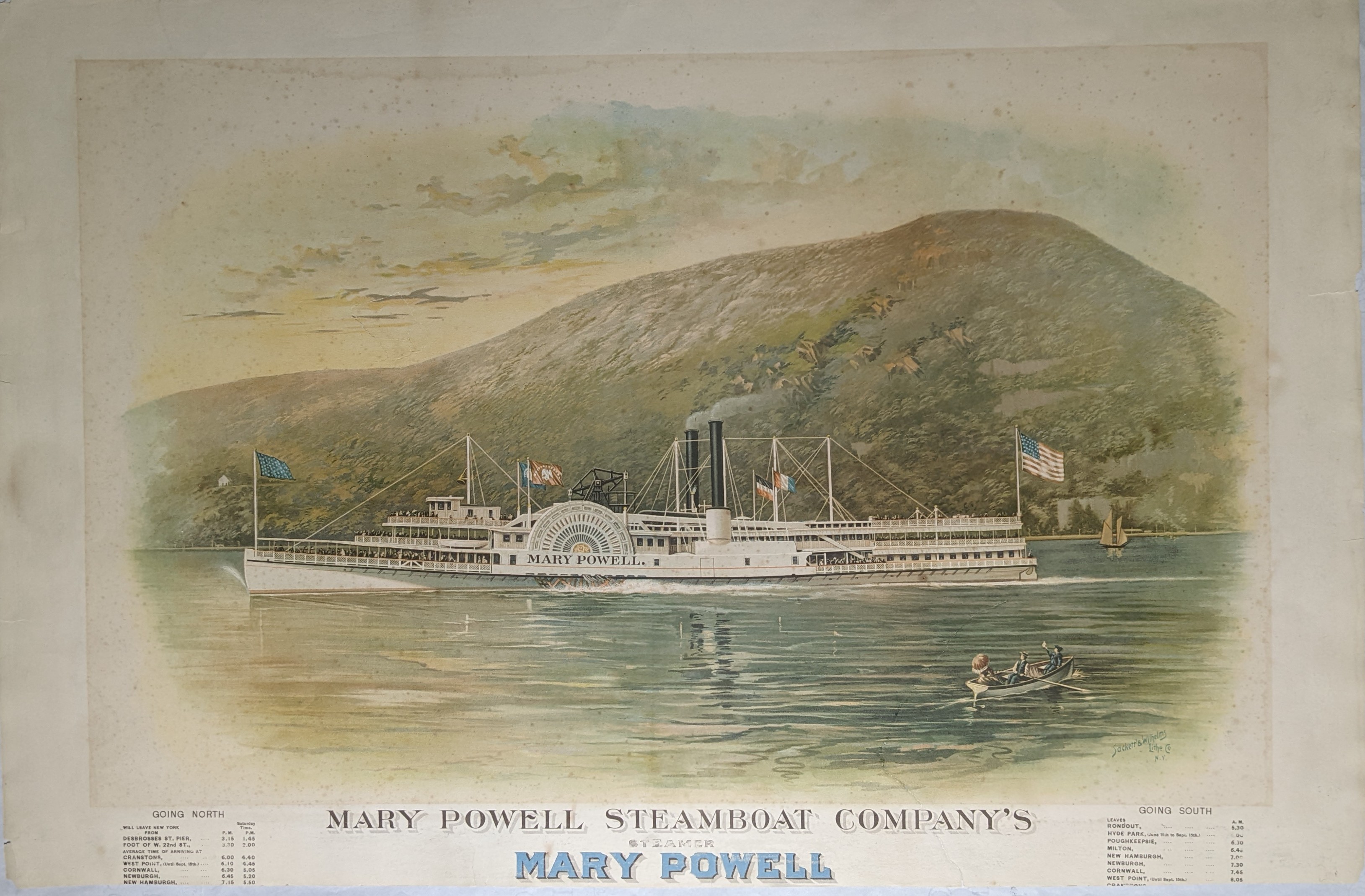

Mary Powell Advertisement Poster with Departure Times, c. 1890-1910 (PHM)

Known during her time as “the Queen of the Hudson,” the Mary Powell, built in 1861, was a famous steamboat along the Hudson River. Named after the widow of Thomas Powell, a businessman from Newburgh, her feats in high-speed travel caused many to believe that she was the fastest river steamer in the world. She joined the Hudson River Day Line in 1902, and slight alterations were subsequently made to modernize her appearance.10

In 1913, the company decided to additionally make the Mary Powell a charter steamer and the Albany replaced her route, which was deemed a sad affair with one newspaper stating that “Clocks stopped all the way down the Hudson River…Everything seemed to be out of sorts.”11 After a brief run in her new role lasting until 1917, the Mary Powell was eventually sold and gutted for scraps in 1920.12

A portrait taken circa 1900 of the crew of the Mary Powell captures Fannie M. Anthony, a Black stewardess of some renown. Anyone traveling on the Mary Powell from 1869 to 1912 would have met this “efficient and obliging stewardess.”13

Overall, the Mary Powell in many respects is representative of a golden age in recreation, demonstrating a point in time when people were eager to get out on the river for a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Her demise marks the beginning to the end of an era. However, despite the setbacks steamboats faced, the Hudson River Day Line continued running into the 1970s.

Great advancements in comfort and the flexibility of expanding railroads began to displace the luxury of steamboats. Additionally, the advent of the automobile provided travelers with more convenience and freedom in their journeys. These other forms of transportation consequently began to crowd out steamboats over time, yet Putnam County and the Hudson River still continued to attract the attention of tourists looking to escape urban life, sedentary work, and mundane days.

For more information and a more immersive look at recreation and leisure in the 19th and early 20th centuries, come visit the current exhibition at the Putnam History Museum, Putnam at Play.

The exhibition will be on display through December 2022, which you can view when the Putnam History Museum is open Wednesdays through Sundays from 12:00 pm to 4:00 pm.

Footnotes

[1] Donald C. Ringwald, Hudson River Day Line, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1965, 77.

[2] Hudson River by Day Light, Albany: Charles Van Benthuysen & Sons, 1898, 23.

[3] Hudson River by Day Light, Albany: Charles Van Benthuysen & Sons, 1898, 17.

[4] Donald C. Ringwald, Mary Powell, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1972, 54.

[5] Donald C. Ringwald, Hudson River Day Line, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1965, 46, 51, 72.

[6] Myra Armstead, “Black History in the Hudson Valley,” 2 October 2021, Hudson River Maritime Museum.

[7] George Wallis, “White Seaman and Cold. [E.g. Colored] Man on Board Steamboat on Potomac, Washington to Aquia Creek Virginia,” Sketches in America, Library of Congress, 26 June 1853, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004662177/.

[8] Marika Plater, “Refuges from Racism Along the Hudson River,” Hudson River Maritime Museum, 2020.

[9] Donald C. Ringwald, Mary Powell, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1972, 85.

[10] Donald C. Ringwald, Mary Powell, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1972, 151.

[11] Donald C. Ringwald, Mary Powell, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1972, 159, 161.

[12] Donald C. Ringwald, Mary Powell, Berkeley, Howell-North Books, 1972, 173, 181.

[13] Sarah Wassberg Johnson, “Fannie M. Anthony,” Mary Powell: Queen of the Hudson, Hudson River Maritime Museum, 2021.